Blog

The “Frozen Spit” Myth: What Cloudy Diamonds Really Are (and When to Avoid)

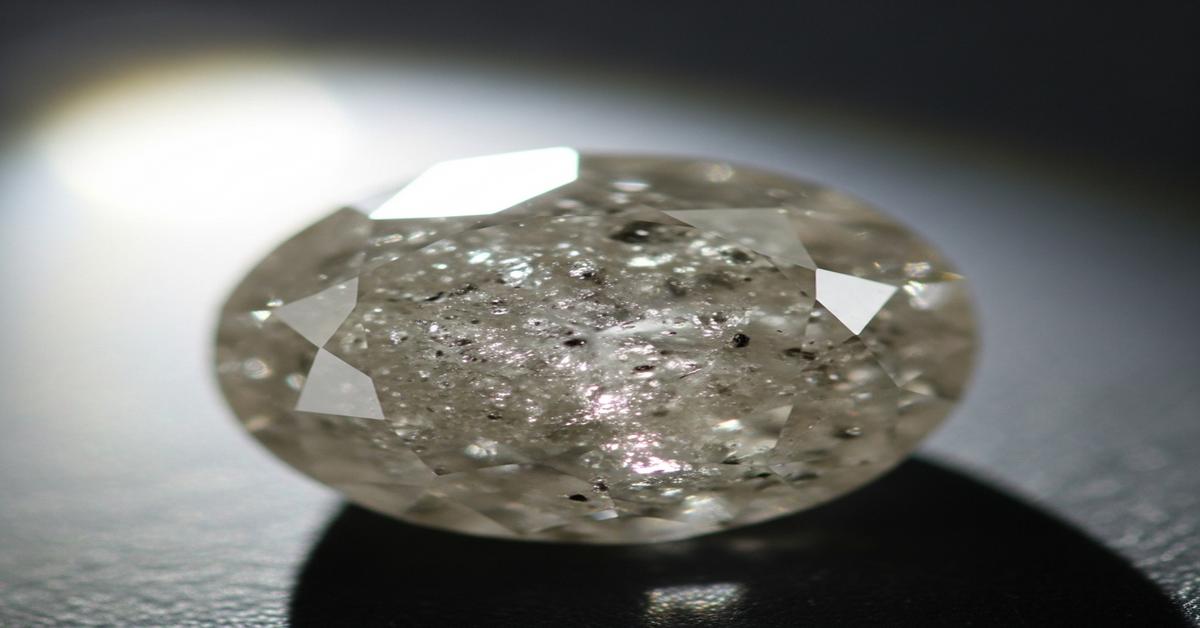

People sometimes describe cloudy diamonds as if a mysterious film has frozen on the stone — the so-called “frozen spit” myth. In reality, cloudy diamonds are not a single phenomenon. The hazy look comes from specific optical or physical issues inside or on the surface of the diamond. This article explains the real causes, how to inspect for them, and when you should walk away from a stone.

What people mean by “frozen spit”

When someone calls a diamond “frozen spit,” they usually mean it looks dull, milky, or like it has a white film across the table. That phrase is a lay description, not a technical term. The look can come from many different causes that affect how light travels through the diamond. Knowing the cause matters because some problems are cosmetic and fixable, while others reduce sparkle, durability, or value.

Real causes of cloudy diamonds

- Clouds (pinpoint clusters). Tiny pinpoints grouped together scatter light and create a soft, hazy zone. These are common in SI and I clarity grades. A 1.00 ct round (≈6.48 mm) with an SI1 grade may have a small cloud that is invisible face-up. But a dense cloud spread across the table makes the stone look milky.

- Internal graining or structural strain. Growth lines or strain can line up and scatter light. This looks like a low-contrast haze and is more likely in lower-grade or synthetic stones.

- Surface haze, residue, or poor polish. Finger oils, soap films, or a bad polish can create a film on the surface. This is often removable with a proper cleaning. A 10x loupe will usually show whether the film sits on the facet surface.

- Strong fluorescence. About 25–35% of diamonds show noticeable fluorescence (often blue). In some stones, strong blue fluorescence in daylight can produce a milky or oily look. For example, a bright H-color with strong blue fluorescence can appear hazy in sunlight because the scattered blue light reduces contrast.

- Fracture filling or clarity enhancement. Filled fractures use glass or resin to mask large inclusions. The fill can cause a soft, cloudy look and may deteriorate with heat or chemicals. These stones are significantly less valuable and must be disclosed.

- Etching, surface-reaching feathers, and damage. Feathers that reach the surface or etched facets scatter light and can cause a persistent cloudy area. These also raise durability concerns, because a surface-reaching feather can propagate under impact.

How to inspect a diamond for cloudiness

- Use a 10x loupe or microscope. Look for pinpoint clusters, feathers, and whether the haze is internal or on the surface. Internal clouds look like blurred patches inside the stone; residue sits on top of facets.

- View face-up and in profile. A face-up view shows how the stone looks in the ring. A profile or side view reveals feathers or clouds near the girdle and pavilion that can affect durability.

- Check under different lighting. Compare LED/white light and daylight. Fluorescence problems often show in strong natural light. Candlelight or warm bulbs may mask clouds because they reduce contrast differently.

- Ask for a video or live demo. A steady, high-resolution video with the stone rotating under light reveals how light returns. A cloudy stone stays dull as it moves; a good stone flashes bright scintillation.

- Inspect certificates. GIA and AGS reports note “clouds,” graining, fluorescence, and any clarity treatments. Look for plotted diagrams and clarity comments.

When to avoid a cloudy diamond

Avoid the stone when cloudiness affects brilliance, durability, or disclosed treatments. Specific red flags:

- Face-up cloudiness that reduces sparkle. If the table area looks milky under normal lighting, this materially alters appearance. For a solitaire engagement ring, this is usually unacceptable.

- Surface-reaching feathers or damage. These pose a breakage risk. For daily-wear jewelry, choose stones with no surface-reaching inclusions.

- Undisclosed clarity enhancements. Resin or glass fills lower value and may fail with heat or ultrasonic cleaning. If it’s treated, price should reflect that — but many buyers prefer to avoid treatments.

- Strong fluorescence causes permanent haze in your lighting conditions. If you often wear the piece outdoors in bright sun and the stone looks milky, don’t buy it.

- Poor polish or residue that won’t clean off. If a jeweler can’t remove surface haze with a proper ultrasonic/steam clean, suspect improper polish or damage.

When a cloudy look can be acceptable

- Vintage cuts, rose cuts, and some antique brilliants intentionally have softer sparkle. A slight haze can suit the style.

- Fashion pieces or heavily-set stones where a halo or bezel hides face-up cloudiness.

- Budget buys where you accept less brilliance in exchange for a larger millimeter size. For example, some buyers choose a 1.50 ct I1 with clouds under a halo to get visual size on a budget.

Practical buying tips

- Insist on full disclosure. Get a lab report and ask about any clarity enhancements.

- Request a real-life video. Prefer a slow rotation under bright light. Look for persistent gray patches.

- Bring a loupe or use the jeweler’s microscope. Learn to spot clouds vs surface residue. Cleaning first is essential.

- Consider setting choices. A halo or pavé can hide small clouds. A solitaire shows everything up front.

- Buy from a jeweler who allows returns. That gives you time to examine the stone in real life and in different lighting.

In short, “frozen spit” is just a colorful way to describe several real optical issues. Some are fixable or acceptable; others damage sparkle, safety, and value. Know what type of cloud you’re seeing, ask for proper documentation and videos, and avoid stones with surface-reaching damage or undisclosed treatments. That way you get a diamond that truly sparkles, not one that looks like a mystery gone wrong.